Bill Atkinson. “The Progress-Index.” Richmond. Legend had it that an image of President Abraham Lincoln lying in his coffin had been placed inside the copper box, but it turned out to be a printed image of a woodcarving memorializing him Researchers at the state Department of Historic Resources began their careful examination Tuesday of about

Bill Atkinson. “The Progress-Index.” Richmond.

Legend had it that an image of President Abraham Lincoln lying in his coffin had been placed inside the copper box, but it turned out to be a printed image of a woodcarving memorializing him

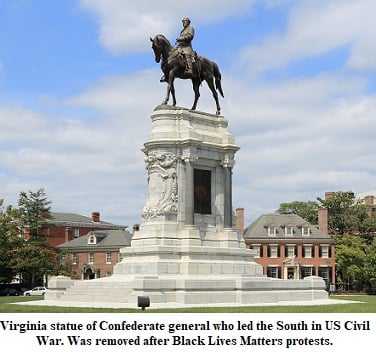

Researchers at the state Department of Historic Resources began their careful examination Tuesday of about 60 artifacts in a time capsule that was placed inside the pedestal of the former Robert E. Lee Confederate memorial. The capsule opened Tuesday was the second collection of artifacts found amid the remnants of the pedestal, which crews began taking down earlier this month. Unlike that first one that contained only a handful of items, this one seemed to be the one that historians were hoping it to be. The capsule opened Tuesday had been documented in an 1887 newspaper article as reportedly containing an image of President Abraham Lincoln in his coffin. Under the direction of state archaeological conservator Kate Ridgway, the 134-year-old copper box was opened at the DHR laboratory in Richmond. The capsule had been found the day before by workers removing the rubble of the memorial on Monument Avenue.

Ridgway said the 14-inch square box looked to be sealed pretty well prior to it being placed inside the statue’s pedestal in 1887. There was some condensation inside the box, but Ridgway said that appeared to be nothing out of the ordinary. Because the box was found in a pool of water, there was concern that some of it might have gotten into it and possibly damaged some of the artifacts. “There does not appear to be much water inside the box, which we are excited about,” Ridgway said prior to the capsule’s opening.

After using a small electric circular saw to remove the top of the capsule, Ridgway and her colleague, Sue Donovan, began sorting through the contents of the 36-pound box clamped to a table in the lab. Using an 1887 newspaper article detailing its contents, the researchers carefully but quickly began pulling out and identifying the contents.

Your stories live here. Fuel your hometown passion and plug into the stories that define it.

The capsule received a lot of early notice prior to its discovery because the article from the Richmond Times-Dispatch claimed that a 1865 picture of Lincoln in his coffin had been placed in it. That image was among the first of the artifacts removed, and it was a centerfold from the April 29, 1865 issue of the Harper’s Weekly newspaper. That centerfold depicted an image of a woodcarving by 19th-century artist Thomas Nast of an unidentified woman grieving over a coffin with the word “LINCOLN” on it. Ridgway said prior to the capsule’s opening that she doubted the authenticity of that report.

Historian Dale Brumfield, one of several involved in the search for the capsule, said the contents “were just about what I had thought they would be.” Like others, Brumfield said he was concerned about the interior’s condition since it was found in standing water, but added the capsule’s creators knew what they were doing to preserve it.

“I was over at the site [Monday] getting ready to do interviews … and for about 10 minutes, it got really quiet over there,” Brumfield said, recalling the moment that the discovery was made. “Then somebody went, ‘Hey, Dale!’ [giving a thumbs-up sign], and I knew that was it.”

In addition to the Harper’s centerfold, conservators uncovered some Confederate money, a button from a Confederate uniform, and a shell fragment from the Battle of Fredericksburg during the Civil War. There were also various books and manuscripts tucked away, including an old directory of the city of Richmond.

Moisture caused a bit of a problem for the conservators as they began emptying the capsule. Some of the books and documents inside had expanded over time and had jammed themselves against the sides of the capsule. Ridgway used the small saw to cut open one of those sides, but only after intense measurements were made to ensure she did not cut into the artifacts themselves. “You really don’t want to cut up the copper box,” she said, “but that’s just how it goes sometimes.

“Using the 1887 article as an inventory list, Ridgway and her team cataloged each item they pulled out, then rushed them into another part of the lab where they would undergo further conservation efforts. Rushing was necessary, Ridgway said, because the longer the artifacts were left out in the open air and under the lights of the lab, the better the chances of them becoming corroded before they could be be further examined. “They had been without any access to any new air and water for over 130 years,” Ridgway said. “So what we are doing is exposing it to air and water, which causes deterioration.”

As an example, Ridgway noted, a silver coin discovered in the first time capsule quickly began corroding as soon as they pulled it out. “Within a minute, it had already turned gray,” she recalled.

However, the first box discovered was made of lead while this one was made of copper. Ridgway said copper acts as a natural fungicide and disinfectant, so even though there was moisture, it was not a major threat to anything. “This really does not smell that bad,” Ridgway joked as she leaned over the capsule.

Just like with the discovery of the first collection, Tuesday’s capsule opening was a major media event in Richmond. Additionally, the capsule’s opening was livestreamed over social media by the governor’s office.

Extreme care was given to the box after its discovery. Once it was brought to the DHR lab, researchers briefly opened it to insert paper blotters that would absorb the condensation before closing it again. It was also wrapped in blankets and blotters to preserve it until the grand unveiling.

Once the artifacts are completely removed from the box, state officials said, they will be further preserved and studied. A determination on what to do with them will be made later.

The Lee memorial, once the crown jewel of Monument Avenue’s gallery of Confederate monuments, was removed last September after the state Supreme Court ruled against an historical group trying to block its destruction. In 2020, Virginia passed a law allowing removal of Confederate monuments from publicly owned land.

Once the rubble is cleared, the state will cede the property on which the statue stood to the city of Richmond.

The statue was often an origination point for last summer’s protests in Richmond sparked by the death of a black man at the hands of Minneapolis police. Demonstrators had tagged it with graffiti, and images of George Floyd, the slain man, were projected onto it.

Bill Atkinson (he/him/his) is daily news coach for USA TODAY’s Southeast Region-Unified Central, which includes Virginia, West Virginia and central North Carolina. He is based in Petersburg, Virginia. Reach him at batkinson@progress-index.com.

1 comment

1 Comment

Frida Masdeu

December 29, 2021, 7:42 pmLee, uno de los mas aborrecibles traidores a su pais junto a Arnold, Rosenberg y el Trompo

REPLY