REQUIEM FOR A DESPOT by Carlos Eire12 . 2 . 16 Dead at last, dead at last. Fidel Castro has shuffled off this mortal coil, at the age of ninety. Unfortunately, his death comes a bit too late—about sixty years too late. Millions of his people had been awaiting this moment for well over half

-

REQUIEM FOR A DESPOT

Dead at last, dead at last. Fidel Castro has shuffled off this mortal coil, at the age of ninety. Unfortunately, his death comes a bit too late—about sixty years too late. Millions of his people had been awaiting this moment for well over half a century. And as we Cubans rejoice, we weep. Our losses over the past six decades have been far too great, and so our glee is far from unbridled.

Slavery is what Fidel’s revolution was about. Brooking no dissent, he enslaved a nation in the name of eternal class warfare, creating a new elite dedicated to suppressing their neighbors’ rights. He pitted Cubans against one another, replacing all civil discourse with invective and intimidation.

Fidel boasted that he was loved by the Cuban people and spoke for us, that he was our very embodiment. But these were some of the boldest of his many big lies. The Cuban people he spoke for were but a monstrous abstraction, a figment that he projected onto the world stage. Flesh-and-blood Cubans had to be forced to attend his interminable speeches, or, as now, his funeral.

Dissenters were demonized. If you objected to his self-anointing as Maximum Leader or disdained his dystopian vision, two painful choices were open to you. Just two.

You could oppose him. But if you dared, even by murmuring in the dark, you faced imprisonment, torture, or death. Hundreds of thousands of Cubans were brave enough to suffer these consequences, but the world beyond the island’s shores ignored them, even denied their existence.

The other option was to beg for the privilege of banishment. Nearly two million Cubans chose that route, but millions more never got the chance. No one knows how many have died trying to escape by sea without his magnanimous permission.

Fidel portrayed those who fled his dystopia as selfish troglodytes. These nonconformists were vilified not just by Fidel but by all those around the world who believed his lies, including many eminent intellectuals, artists, and journalists in free, affluent nations. Lately, the tyrant even seemed to gain approval from His Holiness, Pope Francis, who paid him a very cordial visit.

For the millions of Cubans who remained in Fidel’s kingdom, the losses were even more profound. As they waved tiny Cuban flags at mass rallies and waited in line for necessities with their ration books in hand, as they listened to Fidel’s promises of a very distant glorious future, these Cubans watched others leave by the hundreds of thousands. When nearly two million refugees flee from a small island nation, everyone who remains is touched by loss. The exodus is all the more galling when those who have fled prosper in exile and those who remain become ever more destitute.

Why does the First World display so little indignation over Fidel’s labor camps and prisons, his torture chambers, and the summary executions with which he purchased his shamefully inadequate healthcare and indoctrination programs? Why do so many well-heeled tourists flock to the ruin Cuba has become? Why are so few of them offended by Cuba’s endemic racism, or the apartheid laws that deny ordinary Cubans access to the finest beaches and hotels in their own homeland? And why is it that poor folk from neighboring countries such as Haiti or Mexico have never, ever fled to Cuba?

Fidel justified his repressive policies by insisting that the Cuban people were incapable of achieving social justice by any other means. Likewise, many of Fidel’s First-World admirers view Cubans as postmodern equivalents of Rousseau’s noble savage—as primitives who are uncorrupted by civilization and incapable of comprehending Enlightenment notions of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—or perhaps as swarthier versions of Mussolini’s unruly Italians, that is, hot-blooded Latin rustics in need of a strong leader who can make their trains run on time.

Trying to convince such folk that their condescension toward “persons of colour” in the Third World verges on racism is usually futile. These progressive neocolonialist elites think of themselves as quite different from Ruyard Kipling and kindred bigots of yesteryear. Nonetheless, in order to admire Fidel Castro in our day, one has to overlook his human rights abuses or argue that in benighted places such as Cuba “social justice” can be achieved only through repression. One must assume that those victimized by Castro cannot be “victims,” because they lack the feelings, desires, and reasoning capabilities possessed by those who live in the First World.

How else but by such bigoted logic could Justin Trudeau, the Prime Minister of Canada, propose that a tyrant who impoverished his country and imprisoned, tortured, and executed thousands of his countrymen had displayed a “tremendous dedication and love for the Cuban people”—who in turn “had a deep and lasting affection” for him? Trudeau’s bigotry is subtle but as reprehensible as that of any white supremacist. One must assume that he regards Cubans as inferior to Canadians, for he cannot have been elected Prime Minister of Canada without acknowledging that private property, free speech, elections, labor unions, and a free market economy—all of which are denied to Cubans—are the birthright of every Canadian. If all human beings are equal, then all are entitled to the same rights. This principle, apparently, is lost on Trudeau.

Something very frightening has been made evident in the past few days: the fact that there are many people like Trudeau in this world, who not only are comfortable with the crimes of a cruel despot, but who actually find those crimes praiseworthy.

Fidel’s most amazing triumph was to convince a great number of people around the world that he was a good man, despite all the suffering he inflicted on the people he ruled. Who can measure the suffering he caused? Ask those Cubans whose ranks he has just joined, those thousands he murdered. Ask the thousands who died at sea, trying to escape from him. Ask the dead, yes, if you somehow know how to do so. Ask those hundreds of thousands of Cubans who were crammed into his prisons, and those who were tortured in ways too horrific to imagine, and those who still languish in those dungeons of his. Ask any Cuban who has been forced to attend his interminable speeches, or any Cuban child who has had to spend every summer as a slave in an agricultural labor camp in order to pay for his or her “free” education. Ask any Cuban who has been subjected to an “act of repudiation” by his or her neighbors, or who has in any way run afoul of those other Cubans who run their local Committee for the Defense of the Revolution.

And while you’re at it, ask any Cuban who obeyed Fidel’s baneful commands how they felt about harassing, threatening, and abusing fellow Cubans who disagreed with the Maximum Leader. After all, Fidel did not rule without help. Some ordinary Cubans made his dictatorship possible, indulging their own vainglory. Fidel urged his own people to hate one another, strangling political discourse and poisoning whatever common future they hoped for.

Fittingly, his arrogant deceitfulness extended past his death. In Havana, tens of thousands of Cubans were forced to trudge to the Plaza of the Revolution, to bow before his ashes. Attendance was mandatory—as it was whenever Fidel needed to be surrounded by a throng of slaves—but the ritual was grotesquely hollow. After they had waited in line for hours, all that those Cubans got to see was a small framed photo of the ex–Maximum Leader and a kitschy display of some of his medals, guarded by four young soldiers. The ashes were not there. They were at the Ministry of the Armed Forces headquarters, accessible only to the top brass of the Castro military junta. For a final time, Fidel had hoodwinked his slaves, and the aging oligarchs gathered around his relics probably laughed.

So, good riddance. Let the despot slither into oblivion, along with all his loathsome achievements. History will never absolve him, or those acolytes in charge of his ashes.

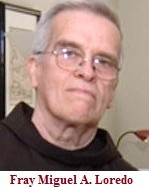

Carlos Eire is T. L. Riggs Professor of History and Religious Studies at Yale University.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *